By Design

The Independent – 21st September, 1998

by Deborah A. Ross

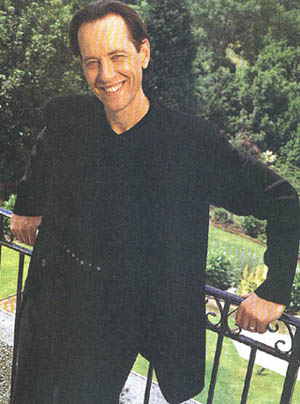

Richard E Grant. Actor, novelist and diarist, whose entry for last Tuesday might have gone something like this: “Tuesday, September 15. To party, to celebrate the publication of my debut novel, `By Design’, at the Pharmacy restaurant and bar in West London. The tiresome girl from `The Independent’, the one my publishers made me have lunch with earlier, turns up. She says: `It’s just like having a drink down your local Boots, isn’t it?’ Pretend I’ve never seen her before in my life. Big, smoochy hug for Celia Imrie, who cries: `Richard! Fab book! How do you do it? Act, act, act, write, write, write…’ I’m all buttery, puppy-pleased until tiresome girl from `The Independent’ asks if this is luvvie-speak for `I hate you, you flash clever-dick’. Nibble something veggie on a little stick. Go home to beddy-byes. Dream that the tiresome girl didn’t tell me off for changing my name. Dream she didn’t say: `Richard Esterhuysen isn’t so bad. It could have been worse. It could have been Richard EstherRantzen.’ Then wake up and realise she did.”

OK, my experience, now. First, the lunch, where I wasn’t tiresome in the least. In fact, I am known to be quite attractive company in the right light and, as for my assertion Richard EstherRantzen would have been considerably worse than Richard Esterhuysen, I think I was pretty much spot on, frankly. Anyway, we meet at Leith’s in Kensington, which is quite smart, and has pleasant, lemon, colour- washed walls, unlike the Pharmacy which has been cleverly designed by Damien Hirst to look, yes, just like Boots. Drinks decanted into medical bottles, bar stools shaped like massive aspirins, huge glass cabinets displaying Anusol, which is just what you want to see when you go out of a night. Richard arrives looking gorgeously dapper in a little riding jacket thingy with velvet collar. He’s attractive in an edgy way, but not especially sexy. Too sunken-looking, like someone forgot to inflate him properly. Indeed, now I think about it, he looks rather like one of those balloons you get from the National Gallery of Munch’s The Scream, after it’s burst. However, being almost as direct and honest as I am untiresome, I decide not to point this out.

Richard says he has just come from home. He has been married for the past 15 years to Joan Washington, the voice coach, and they have a young daughter, Olivia. Richard is entirely devoted to both. He can’t even bear it when, at the later do, Joan strays for a moment from his side. “Where is my wife?” he cries. He played the road manager in the movie Spice World because Olivia begged him to take the part. She is, he says, a huge Spice fan. “She regularly dressed in Laura Ashley little-girl gear prior to the release of `Wannabe’, at which point she was transformed overnight into an eight-year-old slattern.” I say I’m concerned for Baby Spice. What’s going to happen to her when, say, Posh has her baby. Is she going to turn into Jealous Older Sister Spice? Is she going to poke it in the eye, then cry: “It wasn’t me! She did it herself.”

Richard, it turns out, is as worried as I am. He says, even, that having more than one kid is probably a bad idea. “Oh, I see couples with two, three kids and they’re not so much parents, more referees.” Oh, come now I protest, that is going too far. Siblings are, on the whole, good things, blood being thicker than water and all that. He says he has a brother, Stuart, who still lives in South Africa, where they grew up, and whom he hasn’t seen since he was 17. Why not? “Nothing in common.” Did you ever have anything in common? “No. We always had separate rooms, separate schools. Can’t even remember ever playing together.” How bizarre! “Is it?” “Yes!” You see your siblings regularly, then? “I do.” And you get on? “Well, my brother spent most of our childhood writing `Up The Gunners’ in laundry pen on my forehead while I was asleep, but I have long since forgiven him.” I think it’s immensely reassuring, somehow, to have these people about with a shared history. Richard says he just doesn’t need that reassurance which, possibly, he doesn’t. He is quite self-invented in many ways. The big question, when it comes to Richard E Grant, may even be not who he is, but who he once was and isn’t any longer. He is quite complicated, I think.

He can, yes, be a terrifically good actor. Although, that said, his choices are not always wise. Jack and Sarah – yuk! Hudson Hawk, he accepts, was a “great self-basting turkey”, and he never really cuts it as a romantic lead. In the BBC’s forthcoming adaptation of The Scarlet Pimpernel, he is less the dashing hero and more Richard E Grant going about in big cuffs thinking he’s Lawrence Llewellyn Bowen. He was superb as the demented scriptwriter in Robert Altman’s The Player and, of course, brilliant as the down-and-out thespian in the film that launched him, Withnail and I. He is at his best doing manic, panicky, utter-derangement-beneath-the- surface stuff, perhaps because that’s partly how he is. He might never have surpassed his performance as Withnail, actually, and I wonder if this bothers him. I mean when, years later, you are introduced to Steven Spielberg in Hollywood, and he says, “Ah, yes, Withnail”, isn’t it rather irritating? “Absolutely not. Better that than a blank. And it means after you’ve done one thing that’s great, it is your passport,” he says.

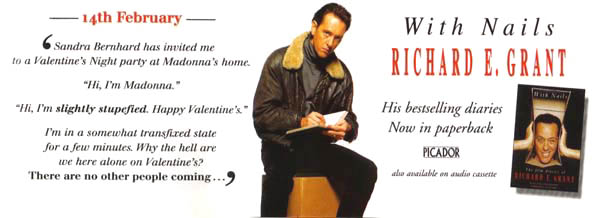

He can also be a jolly good writer. His diaries, With Nails, published last year, are wholly delicious. “25th January. Julian Sands takes me to lunch at The Farmers’ Market…Jodie Foster half- jogs by and comes over as she’s a friend of Julian’s. Lasers me with the compliment she has taken four sets of people to see Withnail and I. Oh, sweet, waffle, syrup thank- you Jodie. My brain is bleating to try and act casual, but body parts have curled up to their toes.” He is really good at getting into the mind- set of the hopeless neurotic luvvie, while being one himself. He can simultaneously be tourist and attraction, which is quite a hard thing to pull off. But – the other thing about Richard – is that he just won’t stick to what he’s good at.

On the strength of the diaries, he has now written his first novel, By Design. It wasn’t something, it transpires, he had a burning desire to do. But after With Nails, “a lot of publishers thought I had it in me to do fiction. There was a bidding war. Picador offered the most… a very lucrative and enticing offer.” The book, subtitled “A Hollywood Novel”, is the tale of Vyvian and Marga, childhood friends from an African country who have always dreamed of Hollywood. To cut a long – exceedingly so, it often seems – story short, they both end up there, he as an interior designer to the stars, she as a celebrity masseuse. Along the way, we are introduced to a cast of washed-up-actresses, on-the-make actors and many other one-dimensional, stereotypical monsters who, possibly, do exist in Los Angeles but just do not come off the page here. It is overwritten in a way that’s OK in diary form, but not, perhaps, in fiction. Talk is “nitroglycerining down the ear of some poor recipient” and, as Vyvian is being seduced, he notes: “Should she guide my now throbbing Titanic into her iceberg, I would definitely be sunk.”

He seems happy with it, though. He did a lot of research in LA. He got a lot of good advice from Steve Martin. “I was going to end it with an earthquake until Steve pointed out that at least three novels this year have ended in earthquakes.” Well spotted, Steve, is all I can find to say.

I think that, sometimes, Richard’s hunger to be someone and stay being someone can work against him. He has always had a great hunger for fame. As a young boy, growing up in Swaziland, he would say to himself: “One day, I’m going to be famous.” Why, Richard? “Because I just didn’t want to be anonymous, I suppose.” At 11, he was putting puppet shows on in his garage. At 14, he was writing letters to Barbra Streisand – c/o Columbia Records – inviting her to stay: “I read in the paper that you were feeling very tired and pressurised by your fame and failed romance with Mr Ryan O’Neal. I would like to offer you a two-week holiday, or longer, at our house…. As such, he now seems to accept pretty much anything that’s offered. It’s like, if you let anything slip through your fingers, then everything might slip away. Thereis, definitely, a kind of panic to him.

He was born Richard Esterhuysen in Mbabane, Swaziland, a tiny country on the eastern edge of South Africa, and part of the British Empire until its independence towards the end of the Sixties, by which time it had filled up with white, colonial refugees. “You know, the sort who had left India, then Kenya, then Zimbabwe, but did not want to go home to Surrey or Sussex, so ended up in Swazi.” His father, Hendrik, was the county’s director of education while his mother, Leonie, worked as a part-time secretary. Mbabane had three streets, a butcher, a baker, a bank and a colonial secretariat. “Of course, everyone knew everyone else. And no marriage stood a chance of surviving more than three weeks, as there was nothing to do except have affairs.”

Mbabane was, he continues, excellent practice for Hollywood. “Being far away from home, people could invent themselves. Everyone seemed to be a character of some sort. There was the lawyer who could recite the whole of Hamlet when drunk, but couldn’t remember a word of it when sober. There was the German ambassador who clicked his heels to attention and knocked off a lot of the Swazi ladies. There was a guy who made rockets which never took off, just skidded along the ground. There was the woman who came around one day, to announce to my father that she hadn’t had sex with her husband for 25 years, like it was some trophy of achievement….” He says he always knew he wanted to get out. And always knew he wanted to be an actor. Escape on all fronts, maybe, was what he was looking for.

The big event of Richard’s childhood came at 11, when his mother went off with a mining engineer, leaving Richard and Stuart with their father. “The social stigma was very acute. Affairs were one thing, but divorce was another. The children at school were very cruel and kept asking where she was. I used to cry at night.” His father, who eventually died prematurely of lung cancer at 51, fell apart. “It was like having to parent your parent.” Although he still saw his mother at regular intervals, the experience changed him fundamentally. “Literally, your world goes in two, and you can suddenly see, unequivocally and cynically, just how the world works. When your parents split up, and then their friends divide and sub- divide – you can see that, as much as you might be involved in something, there might be some other agenda going on. My trust was gone.” Trust in what? “Trust in the family. Trust in things being certain. You become schizoid. You can be part of something, but are aware you are outside, watching, at the same time.” I wonder if this gives him the tourist/attraction quality. He doesn’t doubt it. “In some ways, what happened was hugely beneficial.”

I ask what his mother was like as a person. “She was blonde before she was grey,” he says. What does she make of you never seeing your brother? “Nothing much.” Could you understand how she could leave? “If you are in an unhappy relationship, if it’s a living death, then you have to make sacrifices. I don’t sit in a moral tower of rectitude.” Yes, but as a parent yourself now, can you understand?

“Why do you keep asking me about my mother?”

I’m interested.

“You ask so many questions.”

I’m paid to.

“Well, stop.”

What’s your relationship like with your mother now?

“Leave off my mother!”

Richard, by this point, is enjoying my company so much that, not only does he keep snatching looks at his watch, I think he actually shakes it about at one point to check that it’s still working. Still, he studied drama at Cape Town University then came to London, where he almost immediately met Joan. His marriage, he says, is the most wonderful thing, a kind of reclamation of what was taken from him during his childhood. “Our relationship is as fixed and trusting as a relationship can be.” He has never been tempted to stray. “I probably hold fidelity in much higher esteem than I might have done if my parents had not divorced. To me, it just defeats the object of being with someone if you are going to philander.”

You do get this sense with Richard that, in terms of the self- invention business, he has decided as much who he is not going to be, as who he is. Is there an authentic Richard E Grant? I wonder. Frankly, I’m not so sure but, then, neither is he. “We all wear masks, don’t you think? We get them out at puberty, because the thought of our parents having sex is so horrifying, we have to find someplace to hide.”

Anyway, we have to wrap up now. Richard has “to do a book show on Sky, for my sins.” I tell him I intend to come to the party later. He says: “Oh, good.” Like I said, he can be a terrific actor.

Deborah A Ross. Not an actor, never kept a diary but if she did, the entry for last Tuesday evening might have read: “To Richard E Grant’s do at Pharmacy. `Hello Richard,’ I say. `Oh no, not you again,’ he says. Richard is in full-throttle `Darling, how perfectly splendid of you to come’ thespian mode. Introduces me to his friends as: `Someone who’ll want to know about your mother.’ It’s a monumental celeb fest. Neil Pearson, Kenneth Cranham, Harriet Walter, Peter Capaldi, Samantha Fox, who I bump into by a huge display of Canestan. `In an emergency, you could just break glass,’ I say. `You got frush then?’ says Sam. No, but this would be a handy place to come if I did, I say. `She’s got frush, poor fing,’ Sam announces loudly. Henceforward, have to spend the evening going about bleating `haven’t, haven’t, haven’t’ and, consequently, do not enjoy myself overly. Go home to bed. Dream I forgot to tell Richard that `Esterhuysen’ would not have been as bad as `Esther Rantzen.’ Then wake up and realise I didn’t, thank God.”

The REG Temple is the official website for actor, author and director Richard E. Grant.

The REG Temple is the official website for actor, author and director Richard E. Grant.

Essentially film memoirs, this book chronicles the making of 9 REG movies, but written by REG himself. It’s witty, funny, bitchy and insightful, and a must for any REG fan.

Essentially film memoirs, this book chronicles the making of 9 REG movies, but written by REG himself. It’s witty, funny, bitchy and insightful, and a must for any REG fan.