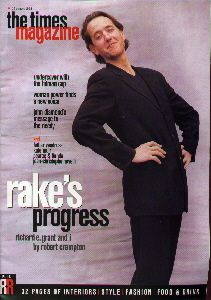

Rake’s Progress

Times Magazine – August 15, 1998

Interview by Robert Crompton

Portraits by Paul Massey

The Outlander:

With his public school vowels and eccentric manner, Richard E Grant has been adopted as the archetypal Englishman. So why does he still feel like an outsider looking in?

I interviewed Richard E Grant in Prague, where he was about to finish four months of filming The Scarlet Pimpernel for the BBC. Usually, you get actors off the subject of the character they are currently playing as quickly as possible. Grant, however, had some interesting things to say about Sir Percy Blakeney, hero of Baroness Orczy’s dreadful but enduringly popular 1905 novel and at least four other filmed versions before this one: Leslie Howard in 1934, David Niven in 1950, Sid James in 1966 and Anthony Andrews in..I don’t know, probably 1982 – Sir Percy seems to saddle up every 16 years. Martin Shaw, who plays the baddy, sums up the subject matter thus: “You have to realise the The Scarlet Pimpernel isn’t A Tale Of Two Cities. Or Les Miserables. It’s more swash and buckle. I did a lot of research before I read the novel and realised that the Baroness hadn’t done any.”

“You could argue,” says Grant, “Why should one care about a man who is saving aristocrats from having their heads cut off? They [the BBC] don’t want the cast of East Enders Bastilling television centre. They were aware in the writing that this is a man who saves other people rather than just saving toffs.” Who may well have deserved what he saved them from? “Yeah.” Unless you argue purely on humanitarian lines? “Right. They’ve had to emphasise that [because] with the collapsing popularity of the Royal Family, going around saving a bunch of French Sloane rangers is not entirely justified at this point in time.”

His diaries (well-edited, published, well-received, two years ago) reveal his own left-of-centre sympathies. How does it feel playing a lickspittle of the ancient regime? “It’s a fictional character, that’s the get-out clause. It’s enjoyable. His ongoing popularity is because he is an 18th-century Batman, leading a double life. The audience knows it, and that’s the kick. Saving people in jeopardy, killing the bad people – these are the foundations of a lot of adventure literature.”

Are you a republican yourself? Grant pauses, starts to waffle, tells the truth. “I grew up in Swaziland, which is a Kingdom and still is. I came to Britain, another Kingdom. But,” he pauses, sighs. “Yeah, I am.”

He says that he has kept the “foppish dandy stuff” to a minimum (although in the scene I saw, it was all “There’s no need to be hasty my dear fellow!” and so forth). Was he playing Sir Percy macho then? Laughs. “It sounds like a contradiction in terms, my name and macho. But yeah, probably more than I anticipated.” He refers a lot to his appearance and physique, or lack of it (he is six feet two and eleven and a half stone, so rake thin). “You are so predetermined by what you look like and how you are physically.” This is an obvious truth of Comerica film-making, but nonetheless not one heard very often from an actor. Later he says: “As an actor…you delude yourself into thinking that you are able to play any kind of part, but there are very few people that do.”

Grant speaks in correct sentences occasionally spiced with expletives. He uses words like “panophy” and “cathartic”, he thinks about what he is saying and he qualifies himself much of the time. He is self-deprecating, and uncomplicated about his profession. He says, for instance, that, unlike Shaw, he did not even embark on any research. “I should lie to you and say I’ve read all the novels the Baroness ever wrote, but I didn’t.”

We spend most of two hours talking about his being an “outsider”. He feels that he is one, and he is pleased and flattering when I latch on to this trait. The thought seemed profound at the time (now it doesn’t because everyone is an outsider to some degree). “I saw Stephen Fry at a birthday party last week – I don’t know him at all – and he said to me, ‘Ah it doesn’t surprise me that you’ve been cast to play this part’ because Leslie Howard was Hungarian or half-Hungarian or his father was or something. Like Baroness Orczy was Hungarian – an outsider writing about England. I had no idea, Leslie Howard is a quintessentially English actor – it had never crossed my mind that he was anything but. Fry sort of pinpointed this thing you’re talking about.”

Grant was born Swaziland, southern Africa, in 1957. We go back to Swaziland throughout the conversation, rather as he now does in life. “The place is magnetic to me.” Indeed, he does seem drawn to talking about it. Indeed, it is probably the most interesting thing about him, I think that he thinks that too. In his diaries he refers to himself, self-mockingly, as The Swaz. He used to sing the Swaziland national anthem at auditions. He wears to watches, one set to Swazi time. He says that “When I meet people who have grown up in Africa like I did there’s an instant bond”.

His father was an education official who stayed on after independence in 1968.

Materially, Richard’s childhood was “a life of privilege which was almost 19th-centruy”. His father impressed on him, however, “That is a white person you were a kind of guest, so you learnt the language and you paid everyone the same respect”. Emotionally, his life was anything but palmy. His parents separated when he was 11 – his mother leaving her family abruptly, for South Africa and another man. Thirty years ago, out in the empire, being the child of divorced parents was a brand-new stigmas. That experience must have toughened him. They get on now, but for years Grant’s relationship with his mother was “very, very difficult”.

His relationship with his only brother still is difficult – or rather, non-existent. They last met at their father’s funeral in 1981, and they did not speak then. “He’s like a cousin that you just don’t see. I don’t feel sadness. If I had had a great relationship and lost it, I might. But I never had one. Nothing in common.” Grant says he will go the rest of his life without seeing his brother “and it is entirely mutual”. True enough: Stuart Esterhuysen does not seem like a man bent on reconciliation with his famous sibling. He told the News Of The World that he though his brother’s wife (Joan Washington, a dialect coach whom Grant met within months of arriving in London, eight years older than he) was, sight unseen, “a complete dog”.

Richard – at this point still an Esterhuysen himself – went to a progressive, multi-racial school and then on to University in Cape Town to study English and Drama. Here, he lost the Esterhuysen on the advice of his tutors (who said it was unpronounceable, which it isn’t) and, utilising his middle name, became plain Richard Grant. The E came in later after Equity told him they already had a Richard Grant on their books.

His voice, he said, has not changed much from his schooldays. “I spoke like a white Kenyan, I suppose. I certainly got ribbed at University for speaking like a toff.” In Cape Town, in the bloody year of 1976, he was, “Like every other student I knew and anyone with half a brain cell”, anti-government. He was in a multi-racial theatre company, and broke a few race laws without ever “attacking policemen or burning the flag”. There were no actors in the family. His father wanted him to be a journalist or a lawyer.

Perhaps his father would have got his wish – Grant obviously adored him – but he died. A year later, aged 25, Grant was in London, set on fame. “I thought if I hadn’t succeeded by 35 I would seriously consider doing another kind of job.” As it was he succeeded within four years, thanks to Withnail and I, a film much admired by many Hollywood players, who have employed him fairly steadily ever since. Turkeys (Hudson Hawk, Prêt A Porter, Spice: The Movie), treats (The Player, Dracula) and potboilers have come along in about equal measure – more turkeys, in truth, in recent years, hence, presumably, how he come to be playing the Scarlet Pimpernel in Prague.

Grant was missing Olivia, his nine-year old daughter, and was anxious to get home. His diaries are full of months in forlorn foreign hotels. The characterless Forum, a couple of miles from the nice bits of Prague, was home to the latest stint. Grant explained succinctly: “We’re here because it looks like 18th-century France but costs them [the BBC] absolutely fuck all. Extras cost nothing. £95 a day in England, £15 here”.

Martin Shaw had taken a flat near the Charles Bridge. I didn’t think to ask Grant why he hadn’t done the same – I think now perhaps he wouldn’t have wanted to be on his own too much. He said “It’s the penalty of this job. There are the obvious advantages, but going away, there’s no way round it.”

Would he refuse a job because it took him away for too long?

A really good part, it doesn’t matter where it is. If it were six months in the Arctic, then short of it being Steven Spielberg, I wouldn’t do it.” Spielberg is a revealing choice his desert island, or polar ice cap, director. If there is a divide among actors between theatre/films; Britain/America; worthy/popular, then Grant comes down firmly on the right hand side of those obliques.

In his diaries, he made it clear that his teenage dream was to be a star rather than an actor per se. He wanted to be in Hollywood, to be famous, to meet famous people, rather than go there reluctantly to pay the rent after 70 years in rep. “Right. where I grew up the tradition of theatre didn’t exist. I grew up on a diet of essentially American movies and American fan magazines. I was starstruck by all that.” Even now, he admitted, “The illusion in a movie is so strong…that if I had a problem, if I had a vendetta to sort out, I’d like to take it to Don Corleone-Marlon Brando, not anybody else. Even though I know how ridiculous that is.”

Through the 1970s, he would watch two films a week at the drive-in – an escape from the pain of his mother leaving, no doubt, but also because there was little else to do. Swaziland did not have television until 1980. When he sees Martin Shaw, he doesn’t think Bodie and Doyle like the rest of us, he thinks Rhodes. So he was cut off from English high culture, but also from the low. During our conversation, a World Cup game was showing in the hotel lounge behind his head. He was not interested, nor felt the need to pretend to be.

“Going back to that snobbery and having to play Hamlet,” he said. “I never had that set of rules in my head.” He has done some theatre, but found the repetition night after night “Mind-numbingly, arse-cripplingly boring). I asked if he considered himself to be a British actor. “Yes.” (Emphatically).

Were the ex-pats in Swaziland more English than the English?

“They certainly were when I grew up. At Christmas, despite the equatorial heat, they stood up when the Queen made a speech, that kind of stuff.” I asked him if he had re- invented himself when he came to London. He said no, not consciously, “That would sound very schizoid”. But people do it all the time, I said. It’s not necessarily a bad thing. “I did think when I came it would be a disadvantage to be so quintessentially middle class.”

I had been thinking that he might have toffed himself up on arrival, but for him, re-invention would have involved proling down – which he certainly has not done. His rather antiquated manners and diction, his rather charm – it all may seem remarkably like a Hollywood version of an English gentleman, but it is genuine, thanks to the ex-pat time-warp. And restricting: “A year ago I desperately tried to get into a film called Face with Robert Carlyle and Ray Winstone. To play an East End psychopath. As soon as I had to speak East End it was just so chronic. I died of embarrassment and shame and apologised to them profusely. I realised absolutely I could not easily transmute into something I am quintessentially not.”

There’s an awful lot of luck involved in what you do, isn’t there?

“I think a huge amount, [although] you can argue that when you have a great piece of luck you’ve got to make good on it.” But for Withnail might you not be here now? “Definitely not.” And how did you make good on your luck? “A friend whom I’ve known for a long time, she said to me that she thought I had an ‘immigrant mentality’. That you had to make the best of what you had without any apology or equivocation whatsoever.” He later says, of the novel (a satire on the Hollywood pecking order) he completed before coming to Prague, grinding it out from 9am to 6pm every day for five months, “If you really want something enough you can sort of get it, unless it’s ridiculous. If I said I wanted muscles like Schwarzenegger it would take a lot of steroids. But it’s possible. But I obviously don’t want that enough to pursue it.”

But you did, and do, want success as an actor enough?

“I think you have to, Robert. I get very impatient with ‘I only want to do interesting work’. Well, I defy anybody to say they want to do interesting work for five people in a chicken shed in the middle of fucking nowhere.” Such a polarisation now looks suspicious, as if he may feel guilty, or frustrated, for not doing more interesting work himself. He went on. “This is one of the most popular mediums ever invented. So getting high falutin’ about it I have almost no patience with. Certainly ten years ago when I first worked in Los Angeles, people said ‘ How can you go to Hollywood?’ I said, ‘Well, if you were offered this, would you turn it down?’ Very few people said ‘ yes I would’.” He thinks that anti-film prejudice has disappeared now that young British actors can pursue film careers straight away, thanks to “Four Weddings showing that British films did not have to be either Merchant Ivory of Mike Leigh”.

So what was it that you wanted to badly?

“What was it that I wanted so badly?” He repeated the question, thinking hard, but knowing that the truth is going to sound lame. “The life of actors – the opportunity to travel, to play different parts – was so fantastical and glamorous, it seemed like a good way of earning a living that wasn’t nine to five. All of that has proved true.” He went on to say that everyone wants approbation, “Actors more chronically than other people”. Insecure? Yes, but the success of his diaries has been “incredibly reassuring and confidence-building”. Vain? “I don’t want to be bald”. (He is receding.) “I’d have somebody else’s face, yeah.”

Around this point a comparison popped into my head, another Pimpernel: David Niven. On reflection, it stands up well enough. Niven, actually a Franco-Scot, also made a good living playing super Anglos for American audiences, was also at his best playing comedy. Niven too was not quite handsome, but charming and disarming, a good chap to have around; not given to nicking the limelight from the A list, bright but unreflective; a lucky lucky man (although not that lucky: Niven’s first wife died at 26; Grant’s first daughter, born prematurely after his wife had three previous miscarriages, died after half an hour).

Niven was also the author of an entertaining, gossipy memoir. I asked Grant if he admired Niven. “He was an actor who was essentially seen as lightweight, for which I can certainly see similarities to my career….I do identify that he never stopped acknowledging how lucky he was and maybe downplayed the fact that he was maybe very skilled as well.”

Perhaps that last bit betrays the slight irritation of a man who feels that because he has realised what lies outside his limitations, he does not get the credit for what he can do within them.

Unlike Niven, Grant doesn’t like to drink, in fact he cannot drink at all, cannot keep it down, and hasn’t tried for 12 years. Nor does he smoke. Nor does he eat meat. But he is a party animal. “I’ve been accused of being off my face many times but you go, by osmosis, with the people that you’re with.”

What about other drugs?

“I have never seen a single person passing round a joint at any Hollywood party. Or pills. Or lines of coke. Just never seen it. obviously it must go on.” He talked about the death of River Phoenix. “Rather than being this big ‘oh such a great talent has been lost’ the people I came across said ‘well the information was out there, the help was out there. if someone self-destructs like that, fuck ’em, it’s their choice.'”

That immigrant mentality again. Grant goes back to his homeland every two or three years, “like a homing pigeon”. “My feeling about being there is incredibly strong, it doesn’t diminish, it increases. It sounds probably very pretentious but the scale of a human being in an African landscape….the sky seems so much more dominant than if you live in a terrace of houses with low cloud cover in the middle of London. The self-importance, or the attention accorded you if you’re an actor, gets out of proportion. There, nobody gives a damn. Nobody knows you from a bar of soap.”

That sounds to me as though he may be looking for something, seeking some purpose in his life beyond being a nice chap and having a nice life. He seeks it here, in films, a little bit; mostly, I think he seeks it there, in Africa, and in his writing. I’m sure it is to be found, Richard’s real purpose, Richard’s real soul, but it proved damned elusive to me.