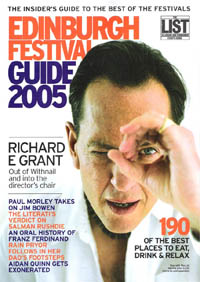

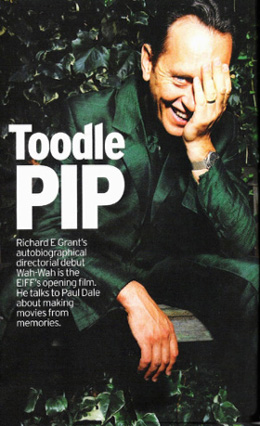

Toodle Pip – Edinburgh Film Festival Guide 2005

Richard E Grant’s autobiographical directorial debut Wah-Wah is the EIFF’s opening film. He talks to Paul Drake about making movies from memories.

They were the days of miracle and wonder. The long distance call. They were the days of medals and shoeshine, and of men called ‘uncle’ even though they clearly had no relation to you, of cricket, warm beer and faltering colonialism. They were the days of Richard E Grant’s childhood in Swaziland – the landlocked kingdom, bounded on all sides by South Africa except for a 110km of border with Mozambique to the east. They were the days of clipped speech and the long, hot, slow wait for Zulu King Sobhuza II to reclaim the country back from London. They were days of ‘toodle pip’, ‘good show’, ‘hush hush’ and ‘trot trot’ and, for young Grant at least, they were the days of ‘Wah-Wah.’

“The film is entirely autobiographical, albeit concertinaed in time with characters and events often amalgamated, but everything happened.” Standing in his west London home, Grant is bubbling with passion, perhaps a little relieved that I do not wish him to perform my favorite bits from Withnail and I. Open and personable, he seems as at ease discussing the factual as the deeply personal.

“You know I developed the facial tic when my mother left overnight; it was very real and a source of acute embarrassment for an adolescent boy. My stepmother essentially ‘cured’ me of it by talking to me about and making me feel secure. But the problem with this kind of nervous habit is that it’s always lurking there somewhere and even now, at 48, if I get particularly stressed, I can feel the ghost of it hovering.”

Since 1985 when Grant made his screen debut in Les Blairs’ advertising satire Honest, Decent and True he has acted in over 60 films. He played a dysfunctional hedonistic actor in Withnail and I, an advertising executive in How to get Ahead in Advertising, an explorer in Mountains of the Moon, a fashion designer in Pret-a-Porter, British royalty in A Royal Scandal, the Scarlet Pimpernel and a priest in Bright Young Things. So it comes as something of a surprise that the man cannot stand to ever watch his own performances back.

“Time and again, people say, ‘But it’s your job, way don’t you like to watch yourself?’ The only way I can explain it is that if you ask people if they like listening to themselves on a tape recorder, they say, ‘Oh God, no’ because that’s not how they perceive themselves. That’s exactly what it’s like to watch yourself and see the faults rather than what other people see…hopefully. It’s the experience of doing it and thinking yourself and feeling yourself into another character’s life.”

It is not difficult to see that for Grant, Wah-Wah, in which he takes no acting role, has been cathartic for a childhood marked by an absentee mother, an alcoholic father and a joyfully unorthodox stepmother. Hoping that by being honest, audiences might both and laugh and be moved by identifying with aspects in their own lives. Grant elucidates in a familiar but slightly too serious tone, Guiding him away from self-aggrandisement, I ask him whether there was any point in the writing of the film when autobiography crossed over into artistic license.

“All the family scenes, including the attempted shooting, happened pretty much as written. The historical liberties taken were necessitated by the three year time scale between 1969 and 1971 of the screenplay. Swaziland’s independence was in fact granted in 1968, Camelot, the play we perform in the film, was in fact staged in 1975, Princess Margaret attended a theatre show and left half way through in 1980. Swazi amateur actors were ‘white’ faced in Gilbert and Sullivan operettas in the mid 060’s, and my father died in 1981 when I was 24. What he said to me on his deathbed is the final line Gabriel Byrne delivers in the film. So I have taken historical license, but the essence of the experience of living there during that era is what I attempted to recreate as authentically as possible. The real challenge of writing about real events is having to edit and truncate them into relatively short scenes. Especially when writing the arc of my father’s alcoholism – having to choose key moments to convey what his schizoid personality was like to live with, when in fact it went on for years with a myriad of variations.”

Grant is no stranger to handling his own backstory with a deft touch. His career memoir, With Nails: The Film Diaries of Richard E. Grant, was one of the more satisfying reads of 1997. He seems to be that curious anomaly amongst thespians: one who respect for the crews he works with goes beyond that he has for his fellow actors. And why not? He has worked with the very best, after all. “Well, I think that growing up and being a teenager in the 70’s, I was influenced by Kurbrick, Coppola and Altman in particular and then having worked as an actor on three Altman films, I was deeply influenced by his regime of being as democratic and collaborative in the way you work.”

Uninterested in pursuing anything but the most personal of cinema behind the camera, Grant is not above that particular luvvie of quoting from the campest of icons.

“I can remember Barbara Streisand talking about when she made her first film as a director,” he gushes. “She said that if it comes from your heart, it goes to the heart. Certainly when I was writing Wah-Wah what I tried to impress upon the actors is that the thing that is most personal to you should reach out in the same way to many more people. I mean essentially Wah-Wah is above love lost, love found, love unrequited, love unresolved, love discovered. And the public face and the private shoe of what family is like, and the disintegration and the survival of my family set against the last disintegrating days of the British Empire.”

Enthused by the success of producing a low-budget film in a seven week schedule (“I was told by every producer I met that we would never make it in time,” he gleefully confides.) Grant was clearly born for this.

“Oh, directing is the most fantastic job in the whole world. If you are as detail obsessive as I am – being asked 200 questions a day was nirvana! I love that. You know: What do I do? How do I do this? Where do I go here? What colour of glass? Where do you what this light? You know, all that stuff. A friend told me a Ridley Scott quote: ‘No matter what you’re asked, always have an answer. Even if you change your mind five minutes later’. I know from my experience of being in films that the greatest compliment that a crew usually pays a director is they that he or she knows exactly what they want. And on day two, I was standing behind a lighting screen and I heard people talking and they said,’What do you think of the guy that’s directing this?’ and the other person said, ‘He knows exactly what he wants!’ and I thought…. well that’s right.”

After talking at some length about the pre-production, editing and funding the film, Grant finally returns to the reason for this beautiful, remarkable little film coming into being. Whatever way you cut it, Wah-Wah is clearly something of a homage, a farwell, a simplification of memory. As he talks, his voice becomes softer, slightly sadder, bur inclusive in it’s willingness to try and understand the sins and subsequent wounds that parents all too often inflict on their children.

As Emily Watson’s character surmises, “It’s called family – you never really get away you know.”

“As a child you totally accept that what goes on behind closed doors is ‘normal’. You love your parents unconditionally, even if one of them runs away and the other practically drinks himself to death. Wah-Wah charts the emergence , I suppose, of adolescent consciousness when you begin to recognize the schism between what is the norm and the abnormal in your own family life and to make choices on your own terms as far as you can. Like a homing pigeon, though, I still feel that Swaziland is my true ‘home’ but know that it is as much a combination of memory, nostalgia and a profound love of the landscape and the incredibly benign and easy going nature of the Swazi people that draws me back there, as much as anything else.”

Grant sighs as the burden of memory seems to overtake him. “I hugely miss the ceaseless flow of characters that fetched up in the colonial era, en route either form India, Kenya, or other outposts of Empire, who had eccentrified by being away from England for too long. Rather like a hothouse, something happens to the English character abroad that prompts all sorts of social and behavioral oddities to erupt. A spirit of gung-ho and make-do that is hugely attractive.”

“The petty snobbery and acute sense of colonial hierarchy and pecking order are mercifully gone, yet they provided an absolute gift for comedy and social gaffes. As my father endlessly pointed out we were only ‘guests’ in the country and with a tiny Europe population amongst a million Swazi, I was never in any doubt that, although born there, I had a ‘sell-by’ date. The AIDS pandemic is catastrophic and the fallout of this time bomb had yet to impact fully. So my feelings about the country are very complicated and contradictory. Exactly like being in love, really.”