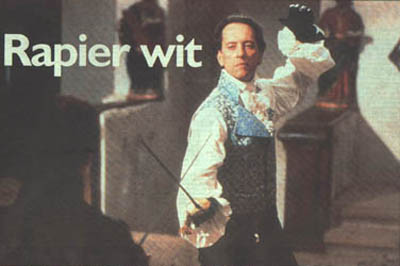

Rapier Wit

The Age Green Guide – 6th May, 1999

They seek him here, they seek him there…

Stephanie Bradbury finds Richard E. Grant armed

with derring-do as the Scarlet Pimpernel.

The Scarlet Pimpernel as whipped up by the BBC, is exactly as you would expect. It swashes, it buckles, it has yards of striped satin and Richard E. Grant saying things like “Odds fish, madame” and smirking. Richard E. Grant’s smirk, I’d wager, could fight a dual on its own. What better actor could there be, pray tell, to fill the buckled shoes of Baroness Orczy’s counter-revolutionary hero than the man who was once Withnail? It is a perfect fit of ham and role.

There are British reviewers who sniff at this sort of thing, but Richard E. Grant is ready with a parry. Every actor, he points out, works within his limitations. As a pencil-thin man over six feet, he is never going to play a bruiser, for example; Sir Percy Blakeney bumped out with a frock coat is about as heroic as he is ever going to get. But what he has in spades, along with Sir Percy, is a particularly English sort of charm.

Which is interesting, because Richard E. Grant is not English. Grant, who used to be called Esterhuysen, grew up in Swaziland, the son of an education official. Like many decent whites from the African plantation belt, Grant is like a throwback to some deleted version of Englishness: courteous, reserved, ironically self-deprectating with a fluted diction that apparently disappeared from these shores the moment they finished making Brief Encounter. Real English charm has to be imported these days.

Indeed, when Grant first arrived in London, aged 25, he worried about sounding too posh. He still has trouble with prole accents; he is currently struggling with Glaswegian for a film about soccer called The Match. Fortunately, he is married to a dialect coach, Joan Washington. He met her within a few months of arriving.

He did have plenty of derring-do to go with the voice, though. Colonial boys learn to ride horses these days, they also bungee-jump and, in Grant’s case, raft down gorges. Whatever his limitations, they perfectly encompassed the Pimpernel. “I was fantastically comfortable with the action because I like horses, swords and all that stuff,” he recalls now, as debonair as ever. “It was like doing what you do when you’re seven, except being grown up and getting paid for it.”

It is a strange thing, expatriation. At 41, Grant is still defined by it. In his very popular diaries, With Nails, he refers to himself as The Swaz; he sings the Swaziland national anthem in auditions, and has his watch set to London and Swaziland time.

Swaziland remains his idyll, the “Switzerland of Africa” where there has never been a revolution or a coup or a famine. It even smells of home.

He goes back every two years. “And it’s very good to go back, because there is no equivalent of First World media or fame,” he says. “So the people I grew up with will say ‘oh yes, I heard you were in something, let’s go and have lunch’. So you forget about all this stuff here.”

And yet, in the manner of expats, he is quite vehemently attached to the most minute details of his adopted country.

The Scarlet Pimpernel was filmed in Prague. They shot for five months. “By the time we came back we were like the Pope, kissing the concrete of Marks and Spencers,” he says. He missed the supermarket, the newsagents, the sense of humour that meant you could “crack a joke without explaining it in a polyglot of bad phrases you’re learned in a foreign language”. He missed Englishness in a way that, perhaps, no Englishman would.

Perhaps this is why he can act English in a way that few Englishmen still can. Why he was selected to succeed Leslie Howard (1934) and David Niven (1950) – as well as Sid James (1966), it must be said – as the dandy whose wit and glowing cravats deflect all eyes from his secret self.

The Scarlet Pimpernel is an unalloyed romantic adventure about a masked hero, which is the only way a leftist republican like Grant can accomodate its unpalatable fondness for tyrannical seigneurs. “I thought of this character like an 18th-century Batman,” he says.

But as adventures go, it is rather camp, what with all that dressing up. Grant says he was often asked if he planned something parodic, something rather post-modern and ironic. He decided against that. “The character is much stronger than the actor who plortrays it. Which is part of the reason for its on-going life.”

And dictates the terms in which it can be played, so performing the Pimpernel becomes a question of measuring up to the archetype. During a week’s shoot in London, Grant was strutting his way through a ballroom scene when an elderly extra approached him. “Of course,” she said, “there is only one Leslie Howard!” “At which point,” says Grant, “I wanted to beat the old boiler to death. But I restrained myself. Because she was absolutely right.”

Possibly. But Richard E. Grant, as well as being terminally self-depricating, admits he has no judgement at all about what he does. “I saw a roughcut of Withnail and I, and I thought I was so bad that I would never get work again.”

He is still utterly mystified by its enduring popularity. “Why should it appeal to people born after the film was made, a film that seems so quintessentially about the 60’s, I have no idea. Male friendship, maybe? The time of those people’s lives? I do remember the dialogue was terribly funny.” It couldn’t have been anything to do with him, surely?

He did get work again, of course. He also resolved never to watch himself on screen if he could avoid it. He says this is not uncommon. “I worked with Judi Dench on Jack and Sarah and she’s exactly the same. She said she’s never seen anything she’s done. And she’s the most incredible actress on the planet.”

That’s the thing; you never can tell at the time. The most enjoyable film he has worked on, he says, was Killing Dad with Julie Walters.

“She is without question the funniest, most extraordinary person I’ve ever worked with, out of a huge number of people. She could make stones laugh, she’s so brilliant. I had an absolute laugh on that. And then the film was an absolute dog. It had the distinction of opening in the West End and three weeks later being a video.”

He has done quite a few dogs when it comes to it, but he seems in good humour about them. Everyone from his manager down told him not to do Spice: The Movie but, he says cheerily, it means that even French children who will never see him anything again can play out whole scenes in front of him – and believe he can speak perfect French. “My credibility with nine-year-old girls is at an all time zenith. I’m enjoying every last nanosecond of it.”

His own daughter, Olivia, is nine, so at least he has done one thing she can enjoy. He is nmot sure how she will respond to The Scarlet Pimpernel; the slashing of heads under the guillotine might upset her, although not as much as the lovey-dovey bits with Elizabeth McGovern. “She thinks the idea of adults kissing is pretty revolting, unless it’s Leonardo DiCaprio.”

Actually, Richard E. Grant is almost as famous for parenting as he is for emigrating. He does say how much he’s champed at the bit to go home to the family, even for a day here and there, when he was in Prague. He seems to feel lonely very easily. He needs to be busy. The diaries, which he writes all the time, fill up a lot of the blank time on a film set, where “people fetch and carry for you, whether you want them to or not.”

Most people don’t notice he’s doing it. “Barbara Hershey, when we were working on Portrait of a Lady, asked me is this on the record or off the record, but she’s the only one.”

At the same time, writing is a lonely activity in itself. The success of With Nails brought a commission for a novel, completed just before The Scarlet Pimpernel began shooting. By Design, to be published in August, is about a celebrity interior designer and a deaf masseuse who infiltrate Hollywood aristocracy.

The second half of the novel, he says, is all about making the most expensive film ever, about the first celebrity passenger ship into space. “So it’s like Titanic meets Alien and then becomes The Posiden Adventure. I obeyed the wisdom that says you should write about what you know. So if you think you recognise anyone, you’re absolutely right.”

He cannot judge this work either, but he says his wife couldn’t put it down. “And she’s very critical. I think she was very worried that I’d write something unreadable or boring or sexist: any of the horrors that would mean someone would come up to her and say, ‘so, you’re married to that fucker? Is this what your sex is like?'”

He is simply amazed he finished it. He was also very relieved to get back to working with other actors. “Having spent four months alone in a room, you become institutionalised, and I am gregarious by nature. Five days a week, eight ’til seven, alone in your own head is not the healthiest way to live.”

The life of Richard E. Grant, all round, sounds packed with glamour. It is, indeed, the life he dreamed as a boy in Swaziland, where there was no theatre, no television and only one radio station. Nobody could imagine why he wanted to act or how on earth he could earn a living at it; his father suggested he become a lawyer or a radio journalist, the only jobs with any performance element within his life’s orbit. “Or mine, for that matter,” says Grant, easily. “The rest was fantasy.”

It It was largely a fantasy of stardom, fuelled by American fan magazines. Richard E. Grant came from the generation that idolised Robert de Niro and Al Pacino; in a tight spot, he told The Times, he would still like to turn to Don Corleone, as played by Marlon Brando, “even though I know how ridiculous that is”.

And he reserved a special fan feeling for Donald Sutherland, “because he had grown up in a tiny town in Canada and he had a very long face and got cast in leading parts, so I was very inspired by him”.

Sutherland proved that you could come from nowhere and be famous. Now Richard E. Grant has proved it again. No wonder he’s smirking.