Clean And Sober

20/20 Magazine – Issue Number 14, May 1990

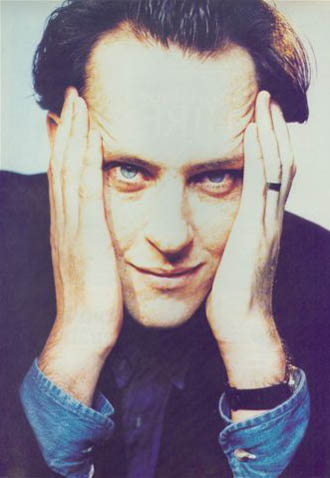

Richard E Grant grew up in Swaziland where days can pass in a haze of Happy Hours. He made his name playing an inebriated out-of-work actor in Withnail and I. But alcohol makes him violently ill and the work is now pouring in.

By Matthew Gwyther Photography by Eddie Monsoon

Richard E Grant was off to the bank to repay his mortgage. It had struck him as odd that he was paying over £5 a day in interest when he could could now afford to buy his East Twickenham house outright. It’s hard to imagine Dennis Quaid, Sean Penn or even Kenneth Branagh trotting off to the Alliance and Leicester. But then Grant is not really like them.

In the past couple of years Grant has been directed by Philip Kaufman and Bob Rafelson. But he doesn’t quite fit the film star part yet: “It’s very odd when you’ve read about these people in film magazines for years and then you meet them on a professional basis,” he says. “I still find it slightly unbelievable.”

It’s not long since Grant was serving in Tuttons wine bar in London’s Covent Garden while trying to get his acting career up and running. “I was a good waiter,” he says, “I don’t drink, which is an enormous plus, and I don’t steal. Those two factors ensured that I remained in the job.”

People find it hard to believe after his performance in Withnail and I that he doesn’t – and never has – drunk alcohol; but it is true. “It makes me violently ill. I’ve tried but it doesn’t agree with me.” Six feet two with a sparkling set of choppers and steely blue eyes, he is also quite the opposite of the dishevelled Withnail. So how had he made the character convincing – did he base it on someone? ‘I, er….Let me put it this way, Bruce Robinson (the director of Withnail and I and How to Get Ahead in Advertising) likes a drink.”

Being brought up in Swaziland also helped.

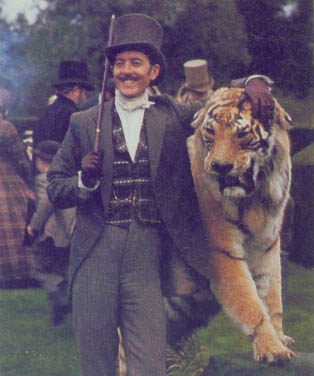

Above: Grant in his latest film, Mountains of the Moon.

“Anybody who’s been to an English colony or protectorate will know that the level of alcohol consumption is enormous. I was in shock when I came to England in 1982 at how little people seemed to drink here. The whole day in Swaziland seemed to be divided up into The Happy Hour. The Cocktail Hour. The Pre-Lunch One.” What of the drugs? Where did he learn of the effects of the Camberwell Carrot, that gigantic reefer Withnail helps to consume in the film? “Swaziland is famous for the quality of the weed grown there and yes, I have partaken of that,” he says.

Grant was born 32 years ago in Mbabane, Swaziland, where his father was director of education in the colonial services. Every now and again you can hear a whisper of southern African in his polished English tones. The young Richard attended the same school as two of Nelson Mandela’s daughters and then went to university 1,200 miles away in Cape Town.

After graduating with a degree and diploma in English and performance, Grant co-founded the Troupe Theatre Company, which worked from Athol Fugard’s Space Theatre in Johannesburg. They struggled on for a couple of years before the idealism died and the enthusiasm, along with the money, ran out. “I had a terrible disillusionment about what I had to offer as a white leftie performing to other white lefties and liberals,” says Grant. “The problems of that country were so overwhelming and I didn’t foresee the system would change at all. I wanted to get out. And there was a fair dose of ambition to have a go at the big time.”

So Grant moved into a Ladbroke Grove flat and, at the Electric Cinema on the Portobello Road, started catching up on the more esoteric Films he hadn’t been able to see in Swaziland. He hadn’t done badly in Africa, though. In a “bug house” of a cinema or at the drive-in down the road, during the early ’80s, Grant had steadily worked his way through A Clockwork Orange, Cabaret, The Godfather, all the early Scorseses and even Last Tango in Paris.

A spell of backstage gofering for Jonathan Miller at the Donmar Warehouse helped get Grant an Equity card plus an arbitrary vowel to fit in the middle of his name – the union already had one Richard Grant on its books. He then did some theatre in Regent’s Park before landing a role in Les Blair’s television play about an advertising agency. Honest, Decent and True, far and away the best dramatic treatment of a profession under excessive scrutiny during the 1980s. Grant played Moonie Livingstone, an affected art director into all things Japanese.

Les Blair’s methods of rehearsal and shooting were unlike anything Grant had experienced before, or since. “Les fostered this sense of paranoia in the cast. Nobody was allowed to speak to anyone else outside the improvised sessions about who the character was or anything. It was perfect for creating an advertising agency. The night before we started filming, Les told us what the story was going to be. We rehearsed for an hour in the morning and then shot it.” Immediately afterwards, Grant took a part in a Vauxhall commercial. “It wasn’t alcohol or cigarettes – a harmless way to spend a day for an enormous sum of money.” And he wasn’t to see much of that for a while.

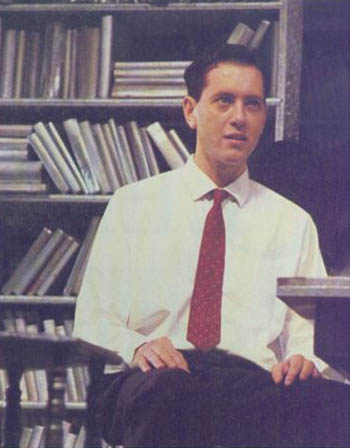

On stage in Tramway Road (1984). He was nominated as Most Promising Newcomer.

“I’d done Honest, Decent and True at the beginning of 1985 and then I was nominated as Most Promising Newcomer for Tramway Road at the Lyric Hammersmith. I foolishly assumed that as I had had a good television break and something in the theatre, a job was bound to come along…..nine months of unemployment followed. I wrote a play, painted and decorated, did odd jobs. You never think it’ll go on for as long as it does.” Thoroughly depressed, at the end of 1985, Grant and his then girlfriend, the voice coach Joan Washington, went their separate ways for six weeks at Christmas. Grant headed for Swaziland, Joan for Scotland. He proposed to her and was accepted at 5am in the arrivals hall at Heathrow. They now have a one-year-old daughter, Olivia.

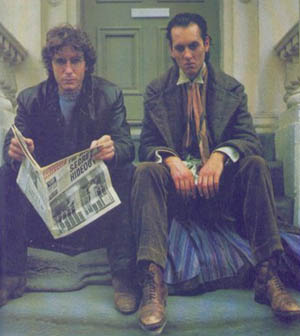

Grant’s professional salvation came in the form of Bruce Robinson, whom he likes to call his fairy godmother. Robinson wanted Daniel Day Lewis to play Withnail in Withnail and I but Day Lewis chose instead to take the lead in The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Robinson still didn’t want to see Grant, but eventually gave him five minutes. They are now good friends. Robinson – at the moment moodily trying to plot a thriller for the “teenage turnips” in America – remembers Grant’s audition. “He wasn’t that good but there was something boiling away there. Richard is quite mad, a bit behind the door.

“I was very strict about the way in which I wanted the lines said,” continues Robinson. “We did a month’s work on them before shooting. But Richard lived or died on his performance. He didn’t resist any risks in that film and really put himself on the line. Every now and again he’d say. ‘Oh, fuck I’m going to appear like a complete cunt if I do this, Bruce’; but he did it.” Grant admits he was terrified of the effect Withnail and I might have on his career. The film, after all, appears slightly short on plot. “I was paranoid that the film would really be the end of it. Nobody could sit through an hour and a half of a man ranting and raving in a drunken state and I was done for. They wouldn’t blame the writer, they’d say ‘That’s old slab-face’s fault.’ Mind you, at the time I wouldn’t have minded playing drunks for the rest of my life if it meant still working. But it worked out fine. And it has always struck me as ironic that playing an out of work actor has led to all this work.”

Robinson offered Grant the role of Dennis Dimbleby Bagley, the manic ad man with the talking boil in How to Get Ahead in Advertising two weeks into shooting Withnail and I. Robinson is the first to concede the film didn’t really work.

“When I watch it now, all I can see are the mistakes,” he says, “We only had 33 days because we had no money. Withnail and I is an incredibly honest film. Advertising wasn’t.” Try as hard as he did. Grant was unable to carry it.

Robinson would like to work with Grant again – “I’d love to have a crack at a play for him. I love his rage. The voice I hear when I write, Richard can articulate. I can’t. I was an actor but a bad one. If I have an argument at a dinner party, I ruin it with the delivery. I always wish Richard would say my words. What Richard needs and deserves is a major part.”

“Bruce is very territorial,” says Grant, “Anything that I do that isn’t with him barely warrants his consideration. It’s a joke between us. We share exactly the same sense of humour and maybe the same sense of anger. But he’s ten years older than me. I certainly don’t have fantasies about decapitated members of the royal family with their heads on stakes lining the Mall.” Grant is also writing a thriller at the moment in his first proper break between acting roles for several years.

Robinson persuaded Grant to spend some of the Withnail and I money on a very fast car – he himself has an Aston Martin DB4 convertible. Grant, however, is uncharacteristically coy about the car he bought. “I can’t tell you.” Not a Porsche? “No.” Is it English? “Stop. stop! I’m not going to tell you!” Oh, go on. “No. It’s not important. It would sound awful. It doesn’t go with being a 98-pound weakling.” Robinson says it’s “some Jaguar”.

All Grant’s film work since How to Get Ahead in Advertising has been American. Released this month is the Bob Rafelson film. Mountains of the Moon. which deals with the trip made by the explorer Richard Burton to discover the source of the Nile in 1860. Grant plays Laurence Oliphant, a publisher and the Machiavelli of the story. Oliphant succeeds in driving a wedge between Burton and his buddy adventurer, John Speke, played respectively by Patrick Burgin and lain Glen, on their return from Africa. Grant is suitably nasty.

Rafelson. who is a bit of an adventurer himself, has previously shied away from dealing with non-American subjects and Mountains of the Moon, despite some accomplished photography in its African scenes, suffers from the problem of being an English subject dealt with by American directors and writers. He found Rafelson good to work for and, “kind of loose. The ’60s were very much his time.”

The film that Grant made with Philip Kaufman, Henry and June, is about the affair in 1932 between Henry Miller and Anais Nin; the latter’s diary recording the event was held back until after her husband’s death in 1985. Grant plays the cuckolded American banker husband.

“Kaufman said he wanted to work with me, but having seen me out to lunch in Withnail and I he wasn’t sure if I could do it. I don’t know if it has worked. We’ll see,” he says. More recently. Grant has been signed to star with Steve Martin in a new film set in Los Angeles. It will be directed by Mick Jackson, a self-confessed Withnail fan.

With the outlook for British films as dismal as usual. Grant wouldn’t mind doing some theatre work. It would mean staying at home÷although with the sort of wages the theatre offers, it wouldn’t make his agent happy. “At the moment, it’s just nice to be at home with the baby,” he says, “and without having to worry about the wolf at the door and the bank manager peering through the letter box.

Mountains of the Moon opens in London on April 20.

As the perpetually drunk actor in Withnail and I (above with Paul McGann) in 1986.

The REG Temple is the official website for actor, author and director Richard E. Grant.

The REG Temple is the official website for actor, author and director Richard E. Grant.