March19

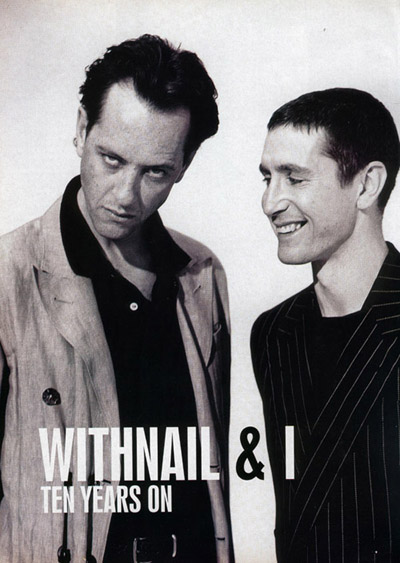

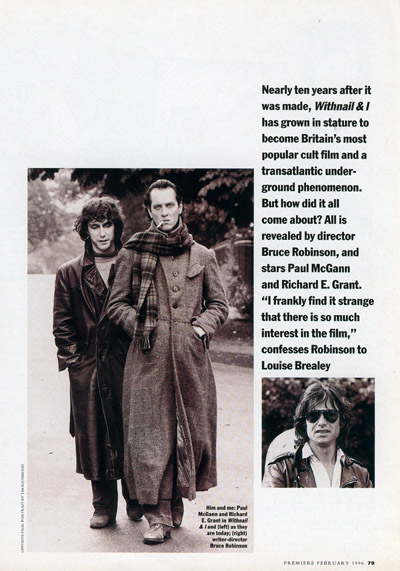

10 years since it was made, Withnail & I has redefined the words “Cult following”. With its infinite amount of quotable lines, it has inspired a generation of drop-outs and one very popular drinking game. David Cavanagh, the world’s biggest Withnail fan, talks to those responsible for the film to ascertain why……

Over the noise of the traffic in Soho’s Frith Street, two men in the upstairs bar of the Dog And Duck are shouting out of an open window.

“Fork it!”

“FORK it!”

The words, which will be familiar to fans of Withnail & I, are particularly meaningful. It was Richard E Grant’s delivery of these very words – at a casting session in Kensington back in 1986 – that convinced writer-director Bruce Robinson that he had found his Withnail. That was a pretty good day.

“Fork it!” shouts Grant, bug-eyed.

“FORK IT!” Robinson yells.

MGM Haymarket. A Saturday night. Two girls filing out of Leaving Las Vegas – and they’re laughing for a start, which can’t be right – notice one of the new posters for Withnail & I as they descend the stairs.

“Oh, I’ve heard of that,” says one to the other. “It’s supposed to be really good.”

“I’ve heard it’s quite funny.”

Eavesdropping on this, the Withnail lover experiences mixed feelings. On the one hand, as a film fan and a nice guy, he is pleased that one of his favourite British movies still commands a powerful word-of-mouth reputation nearly ten years after it was made. He applauds the girls’ open-minded reaction to the film and hopes that they will go and see it.

One the other hand, being an essentially hostile and mean-spirited person, he believes that all prospective converts should be discouraged, as Withnail And I is not a film to be seen by anyone who is not intense or highly intelligent, or who thinks Leaving Las Vegas is a comedy. Then again, he is suspicious of the Withnail cult – he has a lifelong aversion to groups of two or more people who recite movie dialogue in unison – and he believes that the film’s reputation needs rescuing from those who think it’s just an excuse for a drinking game. Having said that, he sees nothing wrong with drinking games in principle, and considers the drinking scenes in withnail to be some of the finest ever filmed.

So what does he do? Stay away, he hisses as he descends the stairs behind the two girls. Stay away from Withnail….

“I think one of the reasons why it’s so popular is it’s one of those films that people find on video through recommendation,” says Ralph Brown, who played Danny. “Somebody says, ‘Oh, you must see this.’ And they watch it and enjoy it and they almost feel like it’s theirs. It’s like a little secret film. I hope that’s not all going to disappear now….”

The Cult Of Withnail And I. It sounds like it ought to be a film in its own right, like The Making Of Michael Jackson’s Thriller. Instead, it is a phenomenon that has slow burned its way across the world. it has made heroes out of the film’s actors. It has spawned a mysterious sect of young men in long coats and scarves, who “feel unusual” and attack their washing-up with forks. It has lured car-loads to Penrith to demand “cake and fine wine” of elderly women in tea-rooms. it has rivalled “This Is Spinal Tap” for sheer tonnage of dialogue-memorising among the addicted. And it has popularised a surname, Withnail, that cannot be found in any phone book.

Nine years after it was first screened, Withnail’s crazy afterlife continues and nobody knows how to stop it. A cinematic re-release has been secured and a competition arranged with Oddbins off-licenses. (“Bring me the finest wines known to humanity…” you are supposed to cry, and they then call the police or something.) Withnail And I posters adorn Oddbins foyers as we speak. The first prize in the competition is a weekend in Penrith, the winner to crash in the actual hotel where Withnail said, “Right, we’re going to have to work quickly. A pair of quadruple whiskies and another pair of pints, please.” Such history. Such devotion.

Upon entering the upstairs bar of the Dog And Duck – a pint of bitter in his hand, a cigarette jammed in his mouth – Bruce Robinson examines the Withnail/Oddbins poster and pronounces the whole procedure rather strange.

Getting Robinson down to London to discuss Withnail is hard enough. Getting him to be serious about it is next to impossible. A skinny, handsome 49-year-old, he has been compared facially to a rock star. An enigmatic man, he seeks to distance himself from any dignity-jeopardising, mad scramble to corral noisy new generations into the Withnail cult. He wonders aloud – as he will do many times today – why all this fuss is being made, why anyone should still be interested in his crazy little low-budget film from so long ago.

(Richard E Grant roars with laughter every time Robinson affects bewilderment. “He told me two weeks into it,” Grant insists, “he said, ‘Grant, we’re making a fucking masterpiece,'” “That’s a load of cobblers,” Robinson retorts.)

Whatever the truth, Robinson is a real character. Knocking back glass after glass of red wine, profaning without regard for slander laws or political correctness, coughing his guts up with each puff of his cigarette, he reduces Grant to helpless laughter time after time. his speech may have a little of Withnail’s aristocratic timbre, but it has every bit of the spleen, the wit and the often mesmerising facility with language. After an especially turbulent cough, he says this, in perfectly-paced Withnail-ese: “From my children I’ve acquired a bit of flu.”

“You sound as it you’re dying,” Grant tells him.

“Why?” he replies. “A little bit of lung cancer, what’s wrong with that?”

“You sound like those two old men on the Muppets balcony.”

“There’s definitely something in there,” Robinson agrees, tapping his throat.

“Some sort of mollusk. But I was reading on the train about that Mitford brother. Sackville-West or whatever his name is. He’s 94, still writing and he’s smoked 60 a day for 80 years. It quite cheered me up.”

And here he is, fulminating fogeyishly on the enduring phenomenon of Withnail copycat behaviour:

“it’s men that like Withnail And I, isn’t it? Young homos. I have seen them! I have seen them! I was coming down the motor way not so long ago, with my wife – sedately driving a Range Rover, as a matter of fact – and we get stuck in a traffic jam. And coming towards us is a Jag with about five Withnails in it. They didn’t realise that you can’t all be Withnail. Buzz!

(Electronically lowering window, leaning out crossly) ‘You’re not all Withnails!’ But they were all Withnails. Of course, if they’d been real withnails, they would have been drunk. the driver was clearly sober.”

The first time Robinson and Grant met was at the aforementioned casting session in 1986. Paul McGann was there, too. He had already been hired as the “I” character (referred to as Marwood in the script but unnamed in the film). The Withnail And I script had built up its own reputation by the time it fell into the hands of the 26-year-old McGann.

“What do they say in literacy circles? It fell like a meteor into a fairground, or something. As soon as it appeared, everyone was going, ‘Have you heard about it?’ Everybody wanted to get down there,” he says, speaking from Vancouver where he is filming Dr Who.

As most Withnail fans now appreciate, the screenplay was based on a novel Robinson had written in 1970 (aged 24) about two drunken, luckless actors.

It was semi-autobiographical: in the 60s, he had shared a terrible Camden Town abode with a self-destructively hard-drinking, inspirational actor friend called Vivian MacKerrell. A good deal of Withnail’s snorting, upper class swagger had been based on MacKerrell, and the 28-year-old Grant was told of this.

“Did he ever get any work as an actor?” Grant asks Robinson now. “That’s the question I’m always asked.”

“Infrequently,” Robinson drawls.

(Mackerrell died of cancer in 1995. Robinson dedicates the new edition of the book of the screenplay to him.)

His novel had set Robinson on the road to screenplay writing. This he did for most of the 70s and 80s. After many disappointments (to this day, only five of his 38 completed scripts have made it to the screen) he wrote the Oscar-nominated screenplay for The Killing Fields in 1984. “It was eminently distressing not getting the Oscar,” he admits.

“Particularly losing it to such a fucking awful film as that Hamlet.” (He means Amadeus) Richard E Grant knew quite a lot about Bruce Robinson. Indeed, as a student in Cape Town in the late 1970s, Grant had stared at Robinson’s face every time he went to the toilet. His (female) flat mate had seen Robinson act opposite Isabelle Adjani in Truffaut’s The Story Of Adele H., and become obsessed by the Englishman’s good looks. She therefore installed a photograph of him in the bathroom. Grant himself saw the majority of Robinson’s 12 films (1968-75). Years later, spotting the name “Bruce Robinson” on the screenplay for Withnail And I, Grant assumed the two men could not be connected. They were.

Robinson was impressed by Grant’s audition – McGann was less sure – and gave him the role on the understanding that he lost weight. Robinson: “I said to the casting director, Mary Selway, I said I’m looking for Byron, not a fucking fat young Dirk Bogarde, which is what his publicity still looked like. (Adopts camp voice) He went on a strict diet, didn’t you? Some kind of protein drink you had, if I remember.”

The two lead actors began a week of intensive rehearsals together at Shepperton Studios. Neither had made a film before. The burden of this one was truly on them. And it was one of the most peculiar comedies either had ever read.

“The thing is,” says McGann now, “when you know it’s meant to be funny, you try and make it funny. And then it’s horrible. So that was the problem, stylistically, for anyone who’s interested.”

“When I first read for him on that first day,” recalls Grant, “he said, ‘Cut the Noel Coward, dear, and start again.’ Because the lines were so epigrammatic, I thought maybe it had to be in that style. “Robinson interjects earnestly.

“All it needs to get the laughs is total honesty. Total belief. If the casting had got fucked up, we’d have failed with the film. it’s so on-the-line. Go too far one way – or too little – and it wouldn’t have worked.”

Once the problem of Grant’s allergy to alcohol had been dealt with – by getting him drunk on vodka and champagne on an all-night bender which, according to McGann, “would outsell Police Stop if it had been filmed” – shooting began on location in Penrith. The producers, Handmade Films, took a solicitous interest in the first day’s rushes, which were necessarily dark (Withnail And “I” arrive by night, enter Uncle Monty’s cottage, light the lamp) and not funny. Over-running by lunchtime on the first day, Robinson was told to cut the bull scene from the film. He resigned instead. Grant was mortified.

“They were just being a gang of cunts fro the first couple of weeks,” shrugs Robinson. “They wanted Uncle Monty to be an effeminate old homo. Fucking nightmare.”

“I’d been telling people I was in this film,” explains Grant. “You first have to get around the title, because they don’t know what it means. “Robinson: “You should try it in Thailand. Witnoh. Witnoh And I.”

Grant: “And then you tell people, it has no plot, no women, nobody gets fucked – there’s an attempted one – and it’s two blokes who are arseholed at the end of the 60s. And people look at you as if you’re some pathetic, desperate case.”

“I’ll tell you exactly why there are no women in it,” Robinson announces.

“If you’re in a state of extreme poverty when you’re young, you literally can’t afford girlfriends. I wanted to use that, in a subliminal way, as a facet of the deprivation. There is no femininity in their lives at all. And indeed in that period of my life, there weren’t any women. I couldn’t afford them.”

“I thought you were with Lesley Ann Down at this point of your extreme deprivation,” interjects Grant.

“I wasn’t with Lesley until 1972. There wasn’t much time for women because it was very much an up-all-night, blokes-talking-and-drinking lifestyle, and girls don’t like that. I remember this friend of mine scored with a chick one night. He washed his sheets literally twice a year. And he got this fucking tube of Mum Rolette that he went over the sheets to get this girl into bed. Because they could not have thrashed into supplication on the banks of the Ganges, these bastards, I tell you.”

Panic over, Robinson returned, as did the scene with the bull. Thereafter – and it’s a curious fact – neither Robinson nor Grant remember there being much laughter on set. You’d expect huge amounts of corpsing, but no, McGann remembers Robinson being very superstitious; if the crew laughed, he’d re-think the scene and start again.

Of all the actors, Grant recalls Richard Griffiths being the only giggler.

“There was only one day that Robinson laughed,” Grant says. “It was a scene in a pub – it wasn’t rehearsed – and I had put a bun or something in my mouth. McGann comes back after the guy’s said, ‘Perfumed ponce.’ And I turned round with a piece of pastry stuck in my mouth, and he (Robinson) literally fell about lighting, and I didn’t know why.”

Grant’s major laughing scene – and one which can be seen in the finished film – came in the Penrith tea-room scene. Robinson had filled the place with elderly local people, without telling them what was going to happen. The atmosphere was interesting, made more so by two dogs situated behind Grant’s chair, who breathed hoarsely and arrhythmically as he spoke. When he reached the line: “And we’ll install a fucking jukebox in here….” he dissolved in laughter.

“Robinson comes over,” recalls McGann, “and says, ‘Great, boys, great, but one thing, Richard, when you get to that line, don’t laugh. ‘Oh, Okay.’ So we did it again and he laughed again. And a third time, and it was getting worse. By 12, 13, 14, Robinson’s livid and Richard’s almost in tears: ‘I’m really sorry, I’m so unprofessional.’ We were going like, ‘Think of your mother dying.'”

“Do you know,” says Robinson suddenly, “I haven’t seen the film for years….”

“Yes you have, you fucking liar!” Grant shouts, outraged. “You watch it once a week!”

One aspect of the script that proved uncannily true to life was the relationship in the film’s last 20 minutes between Withnail and “I”. It mirrored that of Grant and McGann. The scene in the cottage when “I” receives the telegram – and Withnail offers his thin-lipped congratulations – was played from the heart by Grant, who dreaded a return to unemployment when shooting ended, and envied McGann his television success with The Monocled Mutineer.

“You and Paul didn’t get on very well, did you?” Robinson taunts Grant. “I always had a scene of a fission between you. Particularly the night he crashed the car and you got out and said, ‘I’m not being in this scene with a fucking drunk!’ And slammed the car door.”

“I can’t believe you’ve remembered that,” sighs Grant, head in hands.

“That was the arrival at Uncle Monty’s house in the Jaguar,” Robinson goes on, enjoying himself. “Paul had had a few that night. He had to reverse back for another take he ran into something. Grant got out like Merle Oberon, slamming the door with his coat flying.”

“He has my phone number,” says Grant patiently. “I have his. I have seen him. We have eaten meals together. So this Cold War you’re insinuating isn’t true.”

“I’m surprised he didn’t remember the day we were shooting up in Kensal Rise,” McGann says later. “It was the drive out of London, that scene where Richard shouts: ‘Scrubbers!’ We hadn’t really got permission to film and on the fourth take, just as we get to where the crew are, the traffic lights go red. We’re there sitting in this Jag for a minute. And I can see across the road there’s this Panda car. It’s Sunday morning, there’s no one around. I can see the fellow nudge his mate, mouthing, ‘What the fuck is that?’ And I thought, ‘Bollocks,’ and I stood on it and we took off through this red light. And they chased us. And Grant is screaming. He’s screaming in my ear, he’s babbling, he’s talking about being deported back to Swaziland. I’m going, ‘Shut up! Shut up!’ And we get back round to where the crew are – I’m on the pavement doing about 60 – and before I’ve even brought it to a stop, the passenger door is open and Grant’s running for his life. Disappeared down the street. They found him in someone’s garden.”

Down a late afternoon telephone line, the actor who played Danny is thinking back fondly to the three days in 1986 he spent on Withnail And I. “It’s one of the few films I’ve done that I can actually watch and enjoy,” says Ralph Brown. “It still delights me, I’m happy to say. There are lines in it which I enjoy as much as any other fan.”

“Danny didn’t exist,” explains Robinson, “although I did know a drug-dealer called Danny, who’s now a metals dealer in the Stock Exchange. He used to come round at three in the morning. People would lean out of the window to complain and he’s say, ‘Shut your ‘ole!'”

“Danny was a familiar character to me,” admits Ralph Brown. “I come from Lewes in East Sussex and I was a teenager there in the 70s. It was a hippie rocker town. Although I was kind of into Bryan Ferry and David Bowie, a lot of the guys in town had extremely long hair and played in bands and got stoned every night. One particular guy called Noddy used to roll these incredibly long, two-foot spliffs at parties while the younger kinds gathered round and paid homage.”

“I got the voice for him from a hairdresser at Pinewood,” says Robinson. “She was the dumbest bitch you’ve ever met. “I was sitting in on the auditions for Withnails and Dannys when Ralph came in,” laughs McGann. “He was this very soft-spoken, doe-eyed fellow. Bruce said, ‘That’s him!’ I was like, Are you sure, Bruce? In the end they stuck a wig on him and he became Mr Sibilant Brain-Bombed.”

“He’s a very good actor, Ralph,” allows Robinson. “But he’s so unlike the character. He’s quite straight. he’s a bit of a spiv, actually. He used to have an old Vauxhall.”

More hassles with Handmade ensue. They wouldn’t let Robinson shoot the drive back from Penrith to London (this was a disaster: two separate scenes had earlier set up the magnificent piss-bottle payoff) and Robinson was being told to stump up £50,000 per second for using Jimi Hendrix’s Voodoo Child on the soundtrack. McGann believes Robinson paid for this scene out of his own pocket, and also the one that precedes it in the film, where Withnail finishes his lunch in the car. That was shot on the lawn at shopper at a cost, McGann thinks, of £32,000.

“I’ve never known a tenser day,” he says. “That was the worst day on the film.”

That wasn’t all. Once completed, the film was shown to a small, hand-picked audience in the West End so that Handmade could gauge reactions and conduct on-the-spot, Withnail-related market research, e.g: “the scarf – too long?”

Things did not go well.

“Not a fucking titter,” reports McGann, who heard about it later from Robinson. “Bruce is sitting there and he’s dying. No reaction. Uncle Monty appears? Nothing. It’s a morgue. Bruce said it was like The fucking producers.”

According to McGann, events took an upturn when it was discovered that the audience had been composed of non-English-speaking German tourists staying at a nearby hostel.

There is very little unseen Withnail. There was one scene that Robinson filmed that never made it to the screen: a fencing duel in the cottage between Withnail and “I”. McGann, who still has some of the stills, declares it a classic. Grant is smoking beneath his facing mask.

“All you could see was smoke coming out of the bottom of the mask,” McGann laughs. “And he’s, like, flapping about doing this wanky, drama school fencing. it was hysterical.”

Of course scenes Robinson wrote but never filmed, easily the most notorious was his original ending. As he explains, it went like this: “I” packs his things and heads off to the station. Withnail doesn’t accompany him through Regent’s Park. Instead he takes the shotgun which he has brought back from Monty’s cottage, fills both barrels with a 1953 Margot, says, “Chin chin”, drinks from both barrels and pulls the trigger. The plan was to have his death in freeze frame.

“A little too morbid,” Robinson thinks now. It’s tempting to imagine a different life-story for Withnail And I had that ending been the one. Would it have seemed too bleak? would Grant have won a BAFTA? And can any ending really be sadder, anyway, than a rotten actor delivering a rainy soliloquy to an unreceptive wolf?

“That line (of Danny’s), ‘They’ll be going round this town shouting, “Bring out your dead”‘, Robinson notes. “Withnail was one of the dead. The symbolism of the very short haircut, at the end, of the “I” character was based on the horror of Thatcherism coming along.”

Faced with that horror, almost everyone in the film is one of the dead. Certainly, the two most dissimilar characters in the film share a bleak, pragmatic world view that varies only in the phrasing of it. There’s poor, tragic Monty, for whom a golden age has ended. And there’s Danny, who final line reverberates quite menacingly: “And as Presuming Ed here has so consistently pointed out,” he concludes, passing on the Camberwell Carrot, “we have failed to paint it black.”

“That’s true, actually,” Robinson says thoughtfully. “That would have been an interesting scene to have written – between Monty and Danny.” “Not that interesting,” sulks Grant. “I wouldn’t have been in it.”

The badinage is now fast-paced and growing increasingly comical and bitchy. Grant voices the prophecy that Robinson is about to peg out any minute from overdoing the drink and fags. (“Oy-oy-oy,” he shudders as Robinson unleashes the afternoon’s worst cough.) Robinson – regularly switching back and forth between his own voice and that of a preening Soho ponce – rejoins that Grant is nothing but a Hollywood tart, an ungrateful prima donna and, worse, an unfit parent. Grant next reveals that he has written an anecdote in his imminent memoirs about Robinson masturbating into a copy of the Daily Telegraph. (Amazingly, this turns out to be a true story; Robinson vows he’ll sue if it isn’t in the book.) Robinson observes that Grant’s hairline is receding and he will shortly be requiring a wig.

As the discussion creeps closer to Derek and Clive Terrian, Robinson attempts to sum up what it is about Grant that made him perfect for Withnail.

“I don’t know why this is,” he reflects, tussling with a dangerously full glass of red wine, “but somehow the voice I have in mind in my head when I’m writing – this awful, fuck-up,quasi-homo bounder; this vituperative, nasty, acid git (Grant laughs throughout this) – somehow, 7,000 miles away in Africa, Richard can articulate it as an actor. I don’t know why. But he can. He really knows how to hit those moments of spleen.”

“God, that’s going to sound so pretentious,” sighs Grant. How much of Withnail has seeped into Grant’s own personality?

“I’m going to answer that question,” decides Robinson. “I don’t think it’s seeped into him. What it has done is release the latentness of it that was already there, i.e. he’s allowed to exploit it.” He contemplates Richard E for one moment or two. “You’re definitely more Withnailesque than you were when I met you.”

“When I was a terrified, Dirk Bogardian porker,” adds Grant.

“What the fuck is this?” Robinson demands, examining his wine. “I’m only used to drinking quality.”

“You’ve shown admirable restraint, I must say.”

“I have, haven’t I? I’ve only put two of these down, rather than my normal four.”

The good news is that Robinson, far from having retired, has written a film for Grant. It will be the long-awaited follow-up to How To get Ahead In Advertising (1989) and he just has to get it back from Paramount, who appear to own it. McGann reckons Robinson will direct again. So does Grant. Does Robinson?

“No, I mean, fuck me, it’s salutary and horrid, isn’t it?” he laughs, “to think that Withnail And I is probably the only thing I’ll do in my life. Isn’t it?”

“Probably, yeah,” sniggers Grant. “Sad….”

The REG Temple is the official website for actor, author and director Richard E. Grant.

The REG Temple is the official website for actor, author and director Richard E. Grant.