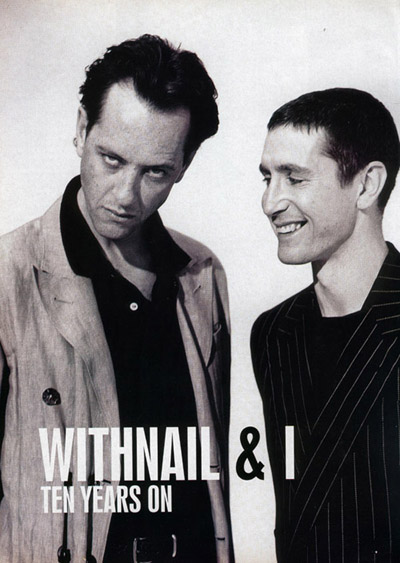

Withnail And I – Ten Years On

Premiere Magazine – February 1996

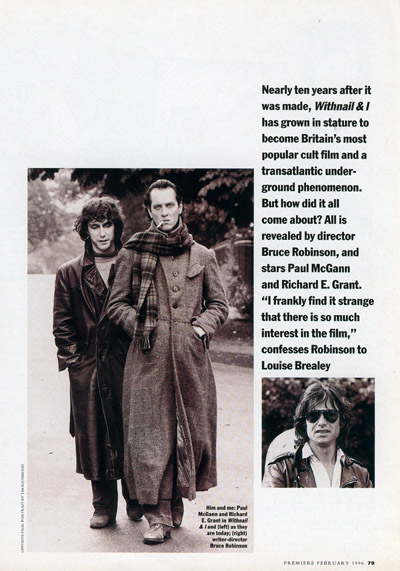

Nearly ten years after it was made, Withnail & I has grown in stature to become Britain’s most popular cult film and a transatlantic underground phenomenon.

But how did it all come about? All is revealed by director Bruce Robinson, and stars Paul Mcgann and Richard E. Grant. “I frankly find it strange that there is so much interest in the film,” confesses Robinson to Louise Brealey.

Dayglo Dreamers, uppers and downers, public sex, The Summer of Love. The ‘60s, right? But the year is 1969 and for some, all is not well with the decade. A well-spoken foul-mouthed pair of struggling actors decide to take time out from their state of almost total squalor for a soul-revitalising jaunt to the Lake District.

Described as “the best England-in-an-acid-bath comedy since the halcyon days of Ealing” on its release in 1988, Withnail & I began its public life as just another moderately successful low-budget offbeat comedy. But rather than expiring gracefully after exiting the big screen, the film eventually went to video, caught the imagination of a generation on a last fling with irresponsibility, and re-emerged as a cult.

Bruce Robinson’s semi-autobiographical yarn about the dog end of the swinging ‘60s first saw the grime of day in a 1970 Camden hovel not unlike the one inhabited by Withnail and his friend. But it languished in a bottom drawer until 16 years later, when George Harrison’s production company, HandMade Films, stumped up the cash.

To celebrate the film’s imminent re-release this month, Robinson and his stars, Richard E. Grant (Withnail) and Paul McGann (Marwood), tell the story of Withnail & I in their own words and muse on why the film has stood every test time has thrown at it to become, among other things, as important a part of student life as Fuck A Fresher Week and finals.

How did Withnail & I evolve?

Bruce Robinson: I went to drama school in 1964, which was a singularly unpleasant experience for me. By my second year I knew I didn’t want to be an actor, but I wanted to be there because of the people who were also there. [My friends] Mickey, Viv, David and myself wound up living in Camden Town with very, very very little money, but with a lot of exuberance and a lot of youth, and a lot of expectation that we would all become film stars, which of course never happened. The environment started to deteriorate, kind of in parallel to the decade, and all these relationships moved on: people were getting married or getting jobs until there was just me and this other guy, Vivian, living in this house.

I went to a secondary modern school, I had no education. Viv was an extremely educated guy, and so I guess in a way he became like a tutor to me: I was constantly asking him about Gerard Manley Hopkins and Keats and Baudelaire and all that. Then he left. He actually got a job, which was almost miraculous, and I was left alone with no money, no food, a gas oven, one lightbulb and a mattress on the floor. It was the winter of 1969. I was desolate, completely in despair. I was an actor and I couldn’t get a job.

So one day I came back to the flat and it was snowing, and I started weeping and screaming at the floorboards. Begging the God of Equity, or any fucking god, you know, to help me. And then it really made me laugh, the predicament that I was in – I laughed hysterically when I thought about it. and I had this old Olivetti typewriter that I used to try and write poetry on. I sat down and I started writing this story about my predicament, involving me and my friend who had now gone.

How autobiographical is the story?

Robinson: The year before I had been on holiday to the Lake District with another friend. (So the friend that I went with wasn’t Vivian, the friend who was Withnail in my head, if you know what I mean.) But it was very much a work of fiction, I wasn’t going round with a tape recorder saying, “Oh there’s a nice line.” I invented it. I had written lots of stuff before then, but all of it real crap. It was the first time that I really found my voice.

How did the novel develop into a screenplay?

Robinson: The book used to go around, people read it and liked it and made photocopies and passed it on. It was like when Russia was still a Communist country and you couldn’t read Zhivago:” underground”. And every time I tried to make it above ground, I failed singularly. I forgot about it. In 1970, a very old friend of mine [screenwriter] Andrew Birkin [brother of Jane], gave a copy to David Puttman, who commissioned me for the first thing I’d ever been paid for as a writer. It was part of a 13-part comedic TV series. This was on the basis of the Withnail book, which he hated, you know, because it was too degraded I suppose for David. But anyway, he gave me this television thing and paid me 200 quid for it. There was this very rich young guy who worked in the oil industry and I think through a friend he read it and came along and he said this is going to make a great movie, and – it must have been around 1980 – he gave me some money to convert it into a screenplay. And then it dropped dead again for about another six years.

When did HandMade become involved?

Robinson: HandMade got involved because an American producer called Paul Heller, who I’ve known for many years, had read Withnail & I and found it amusing, and said, “Well, why don’t you do it yourself?” And concurrently a friend, David Wimbury, who was later line producer on the English side of the production team, took it into HandMade and said, “You’ve got to make this movie, this is a film you can’t afford not the make.” Meanwhile, my producer friend Paul had gone to a property developer in Washington and got half the money for the picture. And George [Harrison, who co-owned HandMade with Denis O’Brien] read it and was very amused by it. And the next thing I was up the hill with a film unit.

How did you cast the leads?

Robinson: The casting was the slowest part. I nearly fired Paul[McGann] the week before we started shooting because of the Liverpool accent. He wouldn’t dump it. He’s very broad, and it was his parachute, his safety padding, you know? If you’re in trouble, some of the lines are quite hard to say in a natural way, and he’d revert to the ‘Pool. And it freaked me out. But from the moment I saw paul I wanted him to play the part. I really wanted a Home Counties boy. So I phoned up his agent to say I wouldn’t be able to use him, just to really frighten him into line. I honestly think that if it had got to a minute to midnight, I would have still had him. But the combination of his and Danny’s [the drug dealer played by Ralph Brown] accents, I don’t think would have mixed very well.

Paul McGann: He never told me anything about the Liverpool accent, because he knows I would have smacked him and given him a black eye [laughs]. No, he may have pulled me aside at one point, but neither of us had ever done a picture, so we were all feeling around. He said, “You can have this job.” And then it was my invidious task – as it turned out – to sit with the prospective Withnails while they were auditioning. I say that because after a day or two, he sacked me. He said, “What are you doing? You’re crap, it’s like Norman Wisdom.” I was so upset. I said, “You’ve got to audition me again”, so he did the following Monday, and then he gave me the job back again.

Robinson: Thank god I didn’t replace him. He was my first choice, although I saw dozens of actors for both parts. I offered Paul’s part to Ken Branagh and he turned me down. He wanted to play Withnail, and I didn’t want him to do that. I didn’t think he had enough nobility. Marvellous actor that he is, there’s something about Ken that is the antithesis of Byronesque; he looks like a partially cooked doughnut. Richard [E. Grant] looks like a fucking Byron, you know. When I met him and asked him to read there’s a line in the film where they’re trying to do some washing-up and he says “Fork it!” about a rotten boiled egg or something. And he did it perfectly and I thought, if he can do that for one line…

Richard E. Grant: At the time I did [the line “Fork it!”] I was lunging at him. He asked me did I generally attack directors and I said, “Not to my knowledge,” and he said wouldn’t I come back the next day and read, which I did with Paul McGann. Then I was called back on Monday to be told that Paul McGann was no longer in the running, and it was now going to be various other people. So I thought, Fuck, I’m going to be used as a kind of stooge to read with other actors while they’re trying to find a replacement. It’s not unusual for that to happen. And then I read with a whole bunch of different people, and [In The Bleak Midwinter’s] Michael Maloney was the favoured one. On Thursday the producer, Bruce, the casting director, Maloney and myself had lunch. I had been out of work for nine months, so I thought, Oh I’ll order absolutely everything on the menu. But the problem was I was so knotted up about whether I was going to get this part or not that it was sort of like eating dog bones. I assumed the whole thing had been a complete disaster.

Anyway, we got to the tube after walking back together and Maloney said, “Oh hold on, I’ve got to call my agent.” So he called his agent in this rush hour and then said that even if they offered it to him, he didn’t want to do it. At this point my jaw was on the floor waiting to be wheeled up. And I said,”Why are you saying that?” He said, “I think this film is anti-gay, anti-black, and anti-Irish.” The whole casting process from the beginning had been to find two people who would be compatible and work together as a team, so, as far as I was concerned, if he was pulling out that put me completely out of the question.

I went down the escalators in an increasing state of depression and then got home, and started blubbing around the place – I know it sounds pathetic – and told my wife, and thrashed round my house, and she said, “Why don’t you just call?” So I called my agent and he said, “I’ve been trying to get hold of you. There’s something wrong with your phone.” And I said “I don’t believe you.” He said, “Yeah, but I’ve phoned British Telecom and they told me your phone was out of order. I’ve been trying to call you since four o’clock. They want to give the part to you.” By this point I was levitating to the ceiling, jumping on the furniture, screaming, shouting. And then he said, “You have to read with Paul McGann.” And it was deja vu, because the previous Friday he had the part and I didn’t, and now the roles were reversed.

McGann: I had heard about a script that was knocking around in the spring of 1986. Actually my agent heard about it first and she said there’s a script which they want to see you for, and it’s about Whistler and his assistant. And I’m like, Oh that sounds riveting. But at the time there were a few Victorian period drama things. I then get the script. So I had to ring her up, and say, “This is not only not about Whistler, it’s brilliant.” I was reading it on the tube, I’m laughing and people are going, What’s he got there?

I’d had this big TV out that year [The Monocled Mutineer]. And when I went to this audition, I hadn’t even sat down and [Bruce] said, “You’ve got the job.” As is the usual practice, they were doing the casting at more or less the last minute. We were to have ten days’ rehearsal and then shoot the film. We didn’t know what we were doing, so it was all a bit fraught, and he couldn’t find a Withnail for some days. Then Richard came in. Bruce said, “What about the South African one?” And I was like, “No, Bruce” And he said, “No, I’m going to get him back.” Well…I couldn’t see it. There had been a couple in the few days that came close. It was a physical thing [Bruce] was looking for. And [Richard] was very nervous himself – he had that imperious bearing and looked down his nose at you.

What about the rehearsals?

Robinson: Richard was quite porky and a tee-totaller, so a very stringent diet was followed by the only time in his life he’d ever been drunk that did the trick. I kept him up and told him, “You have to drink alcohol.” It was vodka and champagne. He hates alcohol. Never drunk, never smoked. We used to give him these herbal [cigarettes] that made him very ill. But otherwise I just totally disillusioned him in every way I could.

Grant: Bruce wanted me to have this Los Angeles bullshit: a “chemical memory”. For a man who is allergic to drink, it is a lot: a whole bottle of champagne in one night. And the next morning they had set up a bar absolutely stacked with these gallon-sized jars of vodka. So I poured one of those lng tumblers three quarters of the way with vodka and topped it up with Pepsi-Cola, drank it down in one and vomited. Paul and Bruce laughed. I just remember them laughing because I was falling around and crying, and laughing completely out of my head. But because we’d had the script drilled into us so resolutely by Robinson, we managed to stagger through three quarters of the whole film all in one room banging out all the speeches. But then I knew I had to get out of the French windows, so I did and a Persian carpet came out of my mouth.

McGann: My fond belief is that he based his whole performance on this. If you’d have seen the raw material – I don’t know who the Oscar went to that year, but… Bruce was panicking. There’s nothing in the world as bad as a bad drunk act – think how pony it could have been! But now look at his eyes, there’s a scene where he shouts out, “Scrubbers” to a group of schoolgirls. He has that madness in his eyes. It wasn’t him. He dictated the pace, he was the soul. He was fantastic when used well, and basically got what he deserved.

What happened when you got on the set?

Robinson: It’s like playing poker when you don’t know how to do it – I was winning all the time. And subsequent to that I’ve always lost because I know the rules. Every hand we all played on the film was right, It’s curious, because on the night before we started filming, I was naturally a little bit nervous and David Wimbury said to me, “It doesn’t matter how good your script is, how good your crew is, if you don’t get luck, you’re fucked.” And we did get luck. everything fitted in and the actors related in exactly the way I wanted them to.

McGann: When we arrived in the Lake District, where we started shooting, we had these adjacent rooms in a hotel with dividing doors between, It’s six, seven in the morning. I can hear next door, bottles clinking, ashtrays shuffling. Then there were noises like a wild animal, these low growls, and then this honey rose tobacco smoke coming between us, and then the door opens and it’s like Boris Karloff, and I’m in absolute hysterics.

Grant: He’s telling you a total lie. I was on a different floor to Paul McGann. You see, I’ve kept a diary on whatever film I’ve done, so whatever they claim they’re probably in for a big surprise when it comes out. Paul and I went to Penrith from Paddington and her started talking about how I was too tall to be an actor, and how all the great movie stars are short arses like himself, and then he quoted Robert De Niro, Dustin Hoffman, all these dwarfs, until I finally summoned up John Wayne. He’s over six foot, and Clint Eastwood is tall, and I said, “Well what about those guys?” And he said, “Yeah, well a couple of pretenders.”

McGann: [Richard and I] had the usual quotient of nerves and a bit of irritation. It was hard going. I don’t recall there being any competition. There were times when I wanted to kill him and I’m sure there were times when he wanted to kill me as well. But there were also times when I was just gobsmacked at what he was doing, and I thought, this tosser can act. He was brilliant in this picture.

At the end of the first week it was going to grind to a halt. There were ructions, as far as I recall, after the first dailies had arrived. I don’t know where Denis O’Brien [George Harrison’s partner and the film’s executive producer] had been -I think he may have been in America – but he was horrified when he saw the first couple of days of dailies. A lot of this was kept from us – a couple of teenage kids who couldn’t bear adult information – but O’Brien’s beef was that this wasn’t the movie that they had commissioned, which is extraordinary.

What he expected, I think, if it’s not being too simplistic about it, was Monty Python. They’d made the Monty Python films, and they wanted something from the same stable. He’d seen Uncle Monty as this fat cartoon character. It was all going to be slapstick and silly walks. It must have been a bit tough for Bruce.

Grant: His [McGann’s] memory’s fucked; it was the first day. This great big gumbah turned up on the set like Sergeant Bilko and ripped out a page of the call sheet, the scene where Paul charges at this bull. And he said, “Right, you’re behind schedule, you can’t do this.” So Bruce said, “Right, fuck you,” and resigned from the film there and then. I had a quiet nervous breakdown over lunch, thinking, Oh I’ve told everybody I’ve finally made a movie and now the thing’s closing down. And David Wimbury, the associate producer, said, “Oh no, it’s just a ploy. The American is trying to frighten Robinson and Robinson is calling his bluff.” Anyway, by four o’clock that afternoon he was directing it again, and the bull scene was put back in.

[O’Brien] told Robinson that I should be playing it like Kenneth Williams, and swinging my arms around and screaming at the top of my lungs; and that comedy couldn’t be done in the dark. Bruce said, “Oh well. You’re wrong. It’s a comedy that doesn’t have any jokes or punchlines. It’s the desperation in the situation where the comedy will come from.” [O’Brien] said the scene where I say, “We’ve come on holiday by mistake,” was not funny. He said it should be nostril-pulling camping around. I said he should have stuck to financing. That really galvanised the whole “us against them”.Robinson: The opening shot was the two guys arriving at the cottage. And I had it in my head what it should look like, and it should be pitch dark. So then [the producers] get in and look at the first day’s rushes and then think, Jesus Christ, what is this guy doing? Second thing was the scene when [Withnail and Marwood] discuss killing the chicken, which when you don’t know the two characters, it’s not funny. It’s like taking an ingredient out of a curry or something and saying, “Is this delicious?” Then here comes Uncle Monty, whom I specifically wanted to play the homosexuality very, very straight. They thought than an effeminate homosexual was amusing, and I didn’t. So there was a walk around this hillside and I said to them, “I’ll get on the bus now and go home: I really do know what this film is and it will be funny. either I’ll walk off now or you’re going to have to trust me and shut up.” And of course they trusted me and shut up. And they were on edge about it until the film came out.

McGann: But people were finding it funny: the crew were falling about laughing. [Bruce] was a bit superstitious about it; he thought if they’re laughing now they’re not going to laugh later, because he’s a worrier. We must have ruined miles of footage just laughing.

Why do you think the film has lasted the distance?

Robinson: I think the thing that makes it leap over the period is the relationship. When you’re young I guess everyone has that kind of intense friendship that has to end, to die. It’s also funny, which helps. I frankly find it strange that there is so much interest in the film.

Grant: I was asked to speak at the Union in Oxford last year – they would have been ten or eleven when the film first came out – so it obviously does keep going, mostly students. They told me in Oxford it’s like losing your virginity – it’s an initiation ritual. If you haven’t seen it you must see it; it’s a prerequisite. And the Etonians thought that it was about them. And the other people thought it was about them, so it obviously crosses over. The young British male. What I have noticed is that it appeals far more to men than it does to women.

What do you think about the re-release?

Robinson: It’s got absolutely nothing to do with me. I’m pleased for them [Feature Film Company, who are re-releasing the film] and I hope they have success with it. From my perspective, and I don’t want this to sound bitchy, but there is a downside to re-releasing the film which is that people discover Withnail and I and it therefore becomes theirs rather than something that has ben marketed and thrust at them.

Grant: I’m very curious about how it does because theoretically, if they re-release a film, you should either be dead or in your advanced dotage. I heard it was going to be December, and then it was going to be January, and I thought it was going to be exactly like the original release. When HandJobFilms, as we called them, made the film in 1986, it took them a year-and-a-half to get it out. I honestly believed it would never come out.

What impact did Withnail have on your career?

Robinson: Everything looked pretty good in terms of making the kinds of films I wanted to make, i.e. comedic little low-budget English films, and then it hit the fan over here and all the companies that financed these types of films liquidated, including HandMade. Next thing I’m in America: Jennifer 8 [Robinson’s 1992 Hollywood thriller] was not a success. A lot of mainstream directors could have done the film a lot better than I. I ended up trying to make an intense European film in an American context. So that was a bad career move.

Grant: I don’t think there is a single film that I have done that hasn’t been as a result of Withnail. That is the thing that has stuck in the head of whoever has employed me.

McGann: I’ve had enduring respect. And on a personal level, complete satisfaction. I don’t wish to sound worthy, but you could go on for years and never do even a remotely good film.

Would you work together again?

Grant: I have to work with [Bruce] again. It’s not a question of would, but when. Unless the stupid fucker drops dead.

Robinson: HandMade are now back in business and I had lunch with a couple of their people the other day. So as soon as this beastly Christmas is dealt with, I’m going to sit down and write a comedy. I’ll probably write a part in it for Richard. It would be lovely to work with him again, but i’d like to do something…maybe not as vicious.

Click the images below to see a larger version of the scanned article.